19. William Hunter's Conceptions

William Hunter, at work among his medical preparations. GLAHA 43793. © The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, 2014. For more, see Exhibit 20, Blank Paper (1).

I ran across this object (above) about three years ago, and had a flash of recognition when I saw it. I was doing research on a project on obstetric anatomy, so was shuffling through the papers of William Hunter, which are held at the University of Glasgow-- where Hunter left his collections and museum. Not much is left of Hunter's papers; he donated his holdings to the University near the end of his life, and had enough time to put things in order. So most of what remains is in his impressive museum of anatomical preparations. It's worth the visit; among other things, Hunter was the man most responsible for ushering obstetrics into the modern age-- for good and ill-- so his surviving medical preparations, many of which detail the processes of generation, can be quite arresting.

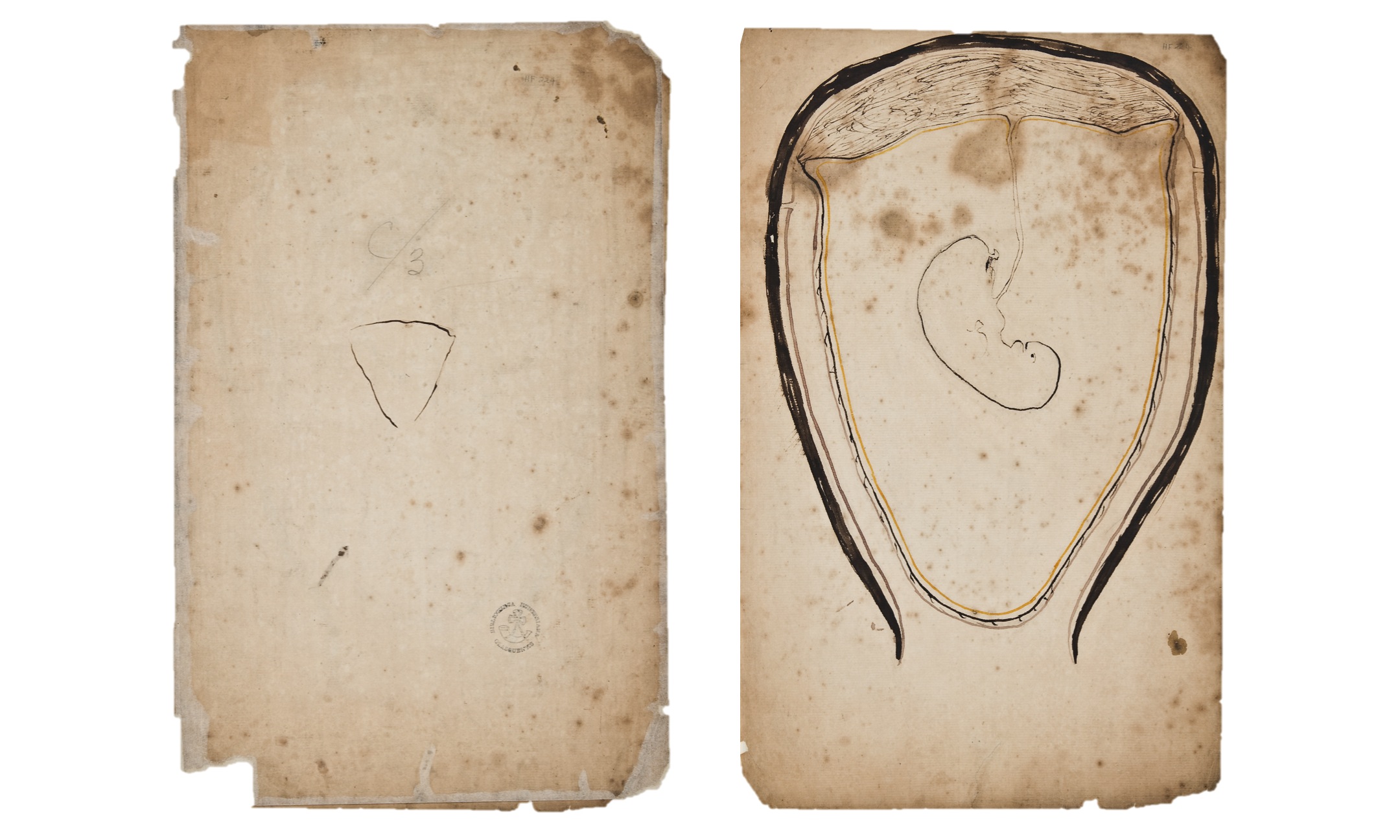

The sheet that forms this exhibit is a single large sheet of paper folded in half. I suspect that Hunter was in the habit of folding paper this way when he meant to use it for quick sketches or the taking of notes; it is a habit I have often observed others using, making a full-sized sheet more portable and compact, better for the small thoughts and small observations that are the stuff of sketches and memoranda. Hunter has folded a single sheet to create a book of the simplest sort-- one sheet made into four total faces. On the first page, the cover of this impromptu pamphlet, are three quick slashes forming a downward triangle; its downward vertex is open. Turn the page, and you find the same general arrangement repeated, but much larger: what is clearly an embryo in the womb, framed by the same geometric outline.

Hunter was an obstetric anatomist; he was an anatomist of one of the most sublime and obscure secrets that anatomy has to offer-- the processes of human generation. This involved him in a number of grisly paradoxes; hunting after the secrets of life involved him in industries of death. He came across the question by accident. He ran a successful anatomy theater in London, working with fresh human subjects that he received licitly and illicitly from the London gray market in cadavers, when he received a double subject-- a woman that died in childbirth. It happened to be in deep winter, which was a stroke of luck, for the cold allowed him to work carefully on this double-specimen without fear of him losing it to spoilage. He, in other words, took his grisly time, carefully distinguishing layer from layer, developing the techniques and insights that modernized obstetric anatomy. Among other things, Hunter was the first to prove that the mother's blood supply was distinct from that of the fetus, which he proved through wax-injections of spider-web delicacy.

"A Foetus at five weeks." William Hunter and Jan van Rymsdyk, Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrata (London, 1774), plate 34.1. Courtesy Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles.

Hunter worked these sketches up into a life-sized atlas. But he wasn't done. He put the call out for more subjects, which he received irregularly over the next fifteen-or-so years. These he worked more rapidly, but rather than displaying a normalized system, carefully distinguished into layers and parts, he instead arranged them as though they were a single specimen. There is, however, a curious feature. He has arranged them backwards in time, such that they retreat (like a flip-book) towards the invisible moment that is the spark of the whole visible machinery. The last of these looks strikingly like Hunter's little sketch on this folio half-sheet; the open triangle, in other words, is a first dash at the outlines of a conception. It is clear that Hunter had started a sketch-- perhaps to explain the rudiments of obstetric anatomy as he understood them-- and found that his drawing was too small for his purposes, so, has turned the page and repeated it much larger.

Six so-called "conceptions," still invisible to the eye, organized as though they were the same conception. They are arranged in reverse order, retreating towards the moment of generation. Hunter, Anatomy, 34.4-9. Image courtesy University of California, Los Angeles.

What is interesting to me, and what drew me to Glasgow in the first place, was Hunter's habit of talking about "conception" in a double sense; by "conception" he means both the rudimentary embryo, and the simplest form of idea. He was not only an obstetric anatomist, but a lecturer at the Royal Academy of Art, where he expressed a deep and delicate understanding of artistic creation-- which clearly crossed with his work in obstetric anatomy. What this page offers us, therefore, is the artist's first idea of a rudimentary embryo: a conception of a conception. It is what conception looks like in an anatomical theater.